Random finds (2016, week 18) — On mind-wandering, deep reading, and why reality is a magnificent illusion

Every Friday, I run through my tweets to select a few observations and insights that have kept me thinking over the last week.

An exploration into our wandering minds

Mind-wandering has recently been undergoing something of a rehabilitation, first in psychological circles, and then more recently in the media. “It is early days yet,” Rowland Manthorpe writes, “but mind-wandering is showing every sign of becoming a thing, buoyed to the surface of popular culture by the overlapping interests of business and self-help. At the root of this turnaround: the idea that mind-wandering is not a waste of attention but simply a different kind of focus.”

Mind-wandering is offered as a complement to mindfulness: “One mental mode is potentially just as beneficial as the other,” as Fast Company puts it. A better question would be: why are these opposing philosophies of mind gaining popularity at the same time? What does it tell us about ourselves that we desire simultaneously to focus and escape? To answer this, it is first necessary to explore mind-wandering’s scientific background. And that’s precisely what Manthorpe does in Mind-Wandering — The Rise of a New Anti-Mindfulness Movement.

“Mind-wandering is one of those paradoxical mental states, like sleep, which is impossible to enter into by conscious effort. To observe it, researchers adopt two main strategies: either they ask people to tell them when they have been mind-wandering; or they give them something to do, then interrupt them to ask if their mind is focused. (Examples of exercises subjects are asked to do include reading War and Peace, taking verbal reasoning tests and listening to Mozart.) Once it’s been confirmed that a ‘task-unrelated thought,’ or TUT, has taken place, then psychologists can examine the neuroimagery to see what was happening in the brain at the time.”

Scientific studies confirm all sorts of common intuitions. We mind-wander most when we are bored, or working at simple, repetitive tasks, such as washing the dishes, or when we are stressed or tired. By delving more deeply into the reasons we drift off, these studies also reveal the benefits of this peripatetic state, whereas previously the costs had dominated the discussion.

Chief among these benefits is creativity. The hidden dividend of zoning out, confirmed by tests on students with ADHD, is an increase in insight and imagination. But mind-wandering also helps us think about the future. When we allow ourselves to tune out, we can wander in time and space, reflecting on past events and contemplating possibilities for the future. It speaks for itself that, in an age dominated by innovation, this combination of creativity and forward thinking is an extremely potent one.

Jonathan Smallwood, reader in the department of psychology at the University of York, and perhaps the foremost researcher in the field, believes that the content of mind-wandering is as important as the context: “It is not mind-wandering per se that we should be focused on when trying to improve health and wellbeing; rather if we want to be happy we should care what we mind-wander about.” In this view, the whole scope of thought seems to be taken into account: what we think, how and why we think it, when and where the thought takes place.

But why are mind-wandering and mindfulness attracting attention at the same time? According to Rowland Manthorpe, the answer lies in our expectations of psychological self-help. “Mindfulness is the perfect plug-in for late modern capitalism: it helps us cope while at the same time making us more productive. And although it might at first glance seem to be very different, mind-wandering has the potential to do the same. We are allowed to drift off, because, if we do it in the right way, then even those breaks are useful. It is okay to waste time, because wasted time is not in fact wasted at all.”

Two more articles on mind-wandering:

- Why we should stop worrying about our wandering minds, BBC Future.

- The Benefits of Mind-Wandering, The Wall Street Journal.

Deep reading for deep thinking

In Read Less. Learn More, Chad Hall makes a case for ‘slow reading.’ According to Hall, people often confuse learning with the collection of data. Learning however, is the process of digestion. It’s what moves something from remembering to knowing. And this is the deepest form of thinking.

We read slowly to ensure that we understand the words in front of us, but we also read slowly with the hope that other thoughts will bleed in.

“Our ability to store information occurs in two main forms. First there is ‘remembering.’ Remembering is basic recall, it relies heavily upon context, takes longer to recall and fades faster. For many of us, remembering is what we used to pass algebra and chemistry. We were able to absorb the periodic table and quadratic equations long enough to pass quizzes and tests but we draw complete blanks hearing those terms now. The other form of learning is what we call ‘knowing.’ Knowing is what occurs when we digest information as truth. It actually becomes a part of us and we can explain it to others.”

“When we ‘remember’ something, we call it data, information or facts. When we ‘know’ something we call it knowledge. Knowledge becomes part of who we are as people. We preserve articles into archives which serve as containers for future retrieval, while the purpose of a book is drastically different. The purpose of a book is to inspire growth. A book is meant to become an addition to our sense of self. And it is here that we find our problem with fast reading: When we begin to view books as something to consume and we challenge ourselves to ingest them faster, we begin to see them as data; as simply something to remember. When we stop looking to them for knowledge everything in them becomes temporary.”

A bit more …

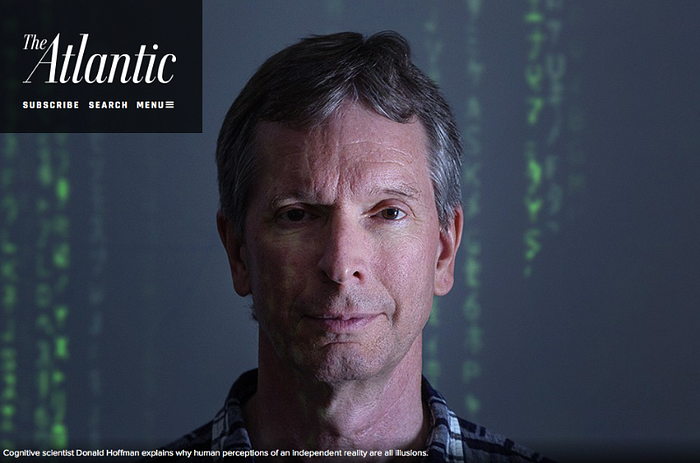

Donald D. Hoffman, a professor of cognitive science at the University of California, Irvine, has spent the past three decades studying perception, artificial intelligence, evolutionary game theory and the brain, and his conclusion is a dramatic one: The world presented to us by our perceptions is nothing like reality. What’s more, he says, we have evolution itself to thank for this magnificent illusion, as it maximizes evolutionary fitness by driving truth to extinction.

Neuroscientists struggle to understand how there can be such a thing as a first-person reality, while at the same time quantum physicists have to grapple with the mystery of how there can be anything but a first-person reality. In short, all roads lead back to the observer. And that’s where you can find Hoffman — straddling the boundaries, attempting a mathematical model of the observer, trying to get at the reality behind the illusion.

Amanda Gefter caught up with Hoffman to find out more.

Read here (The Atlantic): http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/04/the-illusion-of-reality/479559.

More Donald Hoffman in Do we see reality as it is? (TED2015).

In this short film, Charles Eames answers a series of questions asked by Mme. L. Amic of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais de Louvre (1972). Eames’ answers are intriguing.

What are the boundaries of design?

Charles Eames: “What are the boundaries of problems?”

Have you been forced to accept compromises?

Charles Eames: “I don’t remember ever being forced to accept compromises but I have willingly accepted constraints.”

Watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3xYi2rd1QCg.

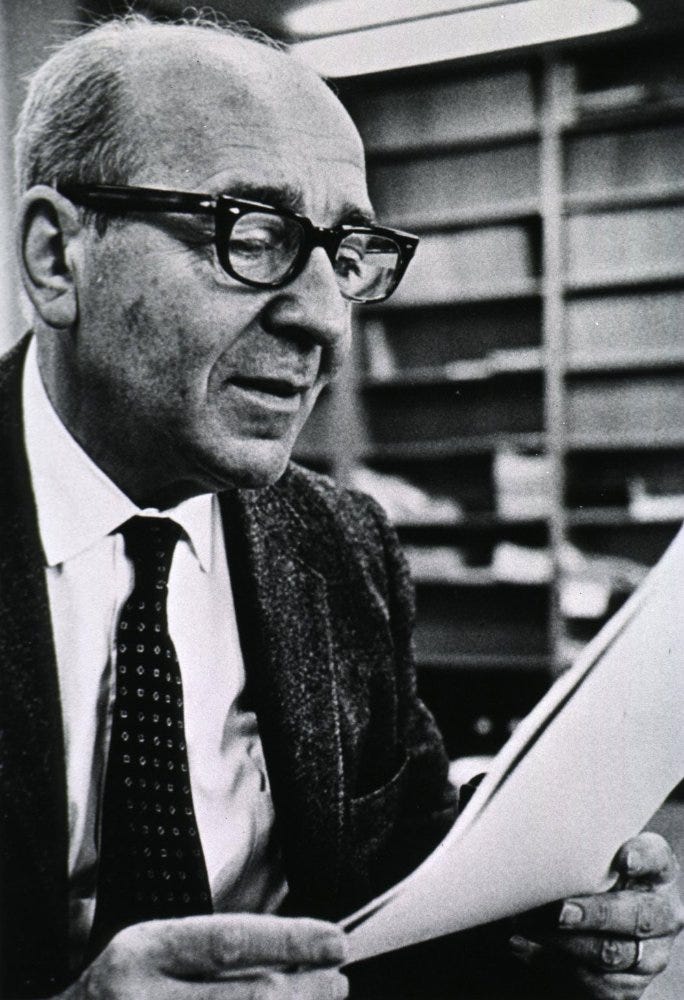

“Creative people live in two worlds. One is the ordinary world which they share with others and in which they are not in any special way set apart from their fellow men. The other is private and it is in this world that the creative acts take place. It is a world with its own passions, elations and despairs, and it is here that, if one is as great as Einstein, one may even hear the voice of God.” — Polish-American mathematician Mark Kac (August 3, 1914–October 26, 1984).

Read here (Brainpickings): https://www.brainpickings.org/2016/05/04/mark-kac-enigmas-of-chance-geniuses/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+brainpickings%2Frss+%28Brain+Pickings%29.

In innovation, the path of least resistance usually leads to mediocrity. A form of Darwinism drives organizations as they decide which ideas to launch. But instead of “survival-of-the-fittest,” it’s “survival-of-the-safest.”

Read here: https://marketoonist.com/2016/05/8-types-of-innovation.html.

“Start-ups wanting to create ‘beautiful organizations’ (as so many founders claim these days) should visit 59-year old Swiss furniture maker Vitra — not just to buy sleek designer office chairs, but to learn from a company culture that actually deserves its title,” according to Tim Leberecht in To Create a Great Company Culture, Start With Culture.

Culture, by its very definition, is thick. Organic, non-linear, unquantifiable, wasteful, messy, and intricate.

“At Vitra, beauty has always had a seat in the boardroom, not just because it designs object of beauty, but because it has a beautiful culture,” Leberecht writes. “Employees are hired not only for functional competence, but for taste and class. One of them told Leberecht, ‘It’s important our partners share our grammar.’ If you define beauty as the harmony between form and feeling, between functional and aesthetic needs, collective and individual wellbeing, as well as the capacity to create unexpected awe, to enchant, then Vitra is a beautiful organization indeed.”

“Practice makes perfect, but it doesn’t make new.” — Adam Grant in How to Raise a Creative Child. Step One: Back Off (New York Times).