Random finds (2016, week 22) — On innovation, life as a video game, and managing without a soul

Every Friday, I run through my tweets to select a few observations and insights that have kept me thinking over the last week.

A ‘mixed bag’ on innovation

Why is Christensen so popular if his theory can’t be put to use? This is the question Jerry Neumann tries to answer in Disruption is not a strategy. “Well, because it can. Just not by you. We are not Christensen’s target audience,” Neumann writes. “The Innovator’s Dilemma was written as a warning to the managers of large companies, the incumbents, not as an instruction manual for startups. For bigco executives, it was a much-needed wake-up call: watch out for those little companies going after the customers you don’t want with technologies that look like toys, they could grow up to displace you. Christensen was not writing to the founders of those little companies on how to disrupt those big companies.”

In this interesting post, Neumann explores why he believes there are better ways than disruption to think about whether you can succeed at building a business with a new technology. In fact, there are few worse ways.

“For most of the entrepreneurs I know,” he writes, “the excitement of building a company comes from working with leading-edge technology, or the smartest engineers, or the hardest-driving customers. When you have these things the temptation is to just start running as fast as you can. When someone asks you how you win, long-term, the easy answer is: ‘we’re disruptive.’ Don’t fall prey to this. You can be right and still lose. Take the time to think about a real strategy. Do it early in the company’s life and revisit it every year, at least. Without a strategy you might predict the market and the technology exactly and still lose to someone who does have a strategy. When I hear the word ‘disruption’ what I hear is ‘I don’t need a strategy’ and that’s a huge mistake.”

In 3 Reasons Why Practice Doesn’t Trump Theory, Tendayi Viki, a strategy and innovation consultant, and co-author of the forthcoming book The Corporate Startup on how large enterprises can implement sustainable disruptive innovation, writes:

“Lean innovation requires cultural and mindset shifts that are often experienced as counter-intuitive by leadership in many large organizations. As our conversations get to boiling point someone in the meeting will inevitably say something like ‘What we do here is not academic. This is a real business, not theory’, or ‘We need practical people in this business, not academics like you. You are too academic to succeed in business’.”

But to Viki, practice doesn’t trump theory; nor does theory trump practice. It’s one of those false dichotomies that people use in order to support whatever agenda they want to pursue. Academic scholars won’t get better unless they understand the real world practice of whatever they are studying. Similarly, practitioners won’t be able to improve unless they understand the principles that underlie and inform their practice. “This is what made Bell Labs great,” Viki writes. “It was the cross-functional mix of academics and practitioners, collaboratively learning from each other and working to make the world better.”

“Theory without action produces armchair revolutionaries. Action without reflection produces ineffective or counter-productive activism. That’s why we have praxis: a cycle of theory, action and reflection that helps us analyze our efforts in order to improve our ideas.” — Joshua Kahn Russell

In 7 Essential Lessons From The Harvard Innovation Lab, Jodi Goldstein, who heads up Harvard’s I-lab, shares some of her lessons learned about how to create an environment where innovation thrives. When she brings in founders to speak with students, she doesn’t want them to share the ‘happily ever after’ version of their stories — she wants to hear about what went wrong and how they handled it. You learn more from mistakes — and from hearing about mistakes — than from successes. She wants her students to know that the stories of overnight successes are often predicated by long periods of frustration and attempts at innovation.

“We all know too well that [immediate success] is the exception, not the rule. That’s what you end up hearing about, but that’s not reality. It’s a long slog, and it takes a lot longer than they think it’s going to be,” she says.

Innovation isn’t lightning; it’s simmering.

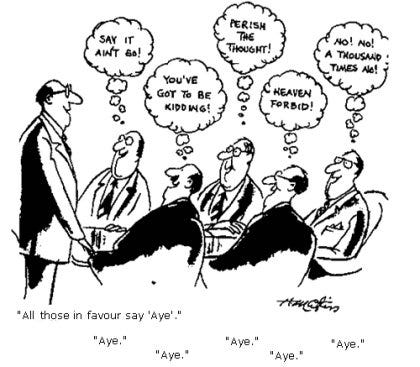

“The problem with following convention is no one ever questions it; consensus-based decisions are very much business as usual,” according to innovation strategist Jorge Barba in Consensus kills innovation. “The ‘coming to consensus’ trap appears when an organization seeks innovation but tries to build group consensus about which new ideas it should support. Consensus-based decision-making can lead to funding only the clearest, safest, or lowest-common-denominator ideas; truly radical projects may raise too many eyebrows to pass through a collective filter. Put simply, consensus can kill risk. Therefore, many innovation funders establish systems that trust the intuition of individuals, while building in feedback loops that can help refine their judgment over time.”

More of this week’s articles and posts on innovation:

- Want to Do Corporate Innovation Right? Go Inside Google Brain, Gregg Satell (Harvard Business Review).

- Lean Startup in the Enterprise — Prepare For A Bumpy Road, Nitzan Merguei (Entrepreneurship World).

- How To Build a Culture of Innovation in Your Organization, Chris Kalaboukis (Medium).

- The 4 Main Ways to Innovate in a Digital Economy, Tucker Marion and Sebastian Fixson (Harvard Business Review).

The only online game that never freezes

The chances are, scientists argue, human life takes place inside a series of concentric, Matrix-style worlds. Maybe we should try to wake up, Julian Baggini, a British philosopher, author of several books about philosophy written for a general audience, and also co-founder and editor-in-chief of The Philosophers’ Magazine, writes in The Guardian.

“Human beings have long been fascinated by the idea that the world as it appears to us is not the ultimate reality. In recent years, however, such metaphysical speculations have taken on a more materially conceivable form. Computer-based virtual reality makes the idea that we could be living in a simulation more than just an abstract possibility; some very smart people even think that this is not only possible, but likely. Very likely.”

“Silicon Valley is a fertile breeding ground for believers, and Elon Musk, the space travel and electric car entrepreneur, has come out as one of them,” Baggini writes. Musk recently revealed the idea that we’re all simulations living in a virtual realm, in a recent interview at California’s Code conference.

The Buddha’s teaching that life is suffering is no less true if rebirth is really a reboot.

But Baggini’s main interest isn’t in whether Musk is right. He is fascinated with the fascination. “Some people just find the whole idea too fanciful to even think about. But many other find it terrifying, exciting or both. Why would such an apparently outlandish idea have this effect?”

“Perhaps the very fact that the theory changes nothing is part of its attraction. You get all the thrill of believing something wild without the downside of having to fundamentally change the way you live. It’s a bold intellectual leap that leaves you exactly where you jumped from. This is the safest possible way to enjoy the exhilaration of upheaval, for there surely is something intoxicating about turning ordinary life on its head, even when it’s terrifying.”

A bit more …

In The Epidemic of Managing without Soul, Henri Mintzberg writes that “managing without soul has become an epidemic in society. Many managers these days seem to specialize in killing cultures, at the expense of human engagement.”

Why do we allow narcissists with credentials, posing as leaders, to bring down so many of our institutions?

“Too many MBA programs teach this, however inadvertently. Out of them come graduates with a distorted impression of management: detached, generic, technocratic. They are educated out of context, taught to believe they can manage anything, whereas in actual fact they have learned to manage nothing.”

Read here: http://www.mintzberg.org/blog/soul.

“At the core of the post-industrial era is the idea that people should take part in designing the important aspects of their life. This principle applies also to the social constructs of work. This may sound radical but comes from the observation that most of the value on a global scale is not created by firms but by ordinary people. People, then, should learn to be better designers. When designing something we always rely on some patterns. We reuse something that is already there. This is important to notice because we are in the midst of a major shift from industrial to post-industrial patterns. Repeating or remixing the industrial patterns do not help us any more,” Esko Kilpi writes in The Design Patterns of Work.

Post-industrial work is learning. It is figuring out how to solve a particular problem and then scaling up the solution in a reflective and iterative way — both with technology and with other people.

“Work starts from problems and learning starts from questions. Work is creating value and learning is creating knowledge. Both work and learning require the same things: interaction and engagement. With the help of modern tools, we can create ways for very large numbers of people to become learners. But learning itself has changed, it is not first acquiring skills and then utilizing those skills at work. Post-industrial work is learning. It is figuring out how to solve a particular problem and then scaling up the solution in a reflective and iterative way — both with technology and with other people.”

Read on Medium: https://medium.com/@EskoKilpi/the-design-patterns-of-work-72f8b4299b10#.rdzpdvgdn.

In one of his Daily Thoughts, Leandro Herrero writes how he had given one of his clients ideas, insights, reflections. “I had shared experiences. I had provided some frameworks, lots of questions and a tour of the misunderstandings. I had pointed out the traps, the risks, the deviations. I had shared the problem of the multiple meanings of the issue. I had drawn a curve of progression from A to B and shared my idea of where they needed to be by now. I told them stories. I gave them examples. I provided them with a suggested list of possible actions.”

“Great!,” they said, but “can you give us something concrete to work with?”

“Oh! Concrete, is a revered word by managers. Ideas, insights, reflections, experiences, questions, possibilities and stories are not concrete enough. Not until you show the 1,2,3, the top 3 take-away, the 5 key actions.”

Unfortunately, Herrero’s ‘concrete’ experience sounds all too familiar.

What is prosperity, where does growth come from, why do markets work, and how do we resolve the tension between a prosperous world and a moral one? These are questions raised by Nick Hanauer and Erik Beinhocker ask in their fascinating long read Capitalism Redefined (2014).

On the difference between efficiency and effectiveness, Nick Hanauer and Erik Beinhocker write that “the orthodox economic view holds that capitalism works because it is efficient. But viewing the economy as an evolving complex system shows that capitalism works because it is effective. In fact, capitalism’s great strength is its creativity, and interestingly, it is this creativity that by necessity makes it a hugely inefficient and wasteful evolutionary process. Near one of our houses is a site where each year, someone would open a restaurant only to see it fail a few months later. Each time, builders would come in, strip out the old furniture and decor, and put in something new. Then finally an entrepreneur discovered the right formula and the restaurant became a big hit, which it is to this day. Finding the solution to the problem of what the local residents wanted to eat wasn’t easy and took several tries. Capitalism is highly effective at finding and implementing solutions, but it inevitably involves trial and error that is rarely efficient.”

Capitalism is highly effective at finding and implementing solutions, but it inevitably involves trial and error that is rarely efficient.

“The genius of capitalism is the way in which it rewards people for solving other people’s problems. People who effectively solve large problems for a large number of other people can be massively rewarded. Steve Jobs made a lot of people’s lives better through the products his company created, and he was highly rewarded for it. As Adam Smith observed 230 years ago, a thoughtfully managed and regulated capitalist economy harnesses people’s self-interest to the broad interests of society.”

Read on Democracy: http://democracyjournal.org/magazine/31/capitalism-redefined.

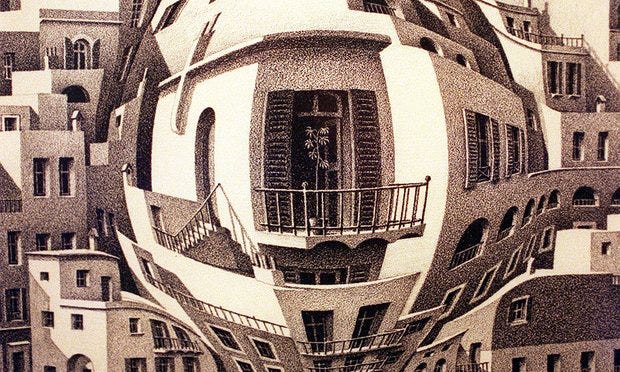

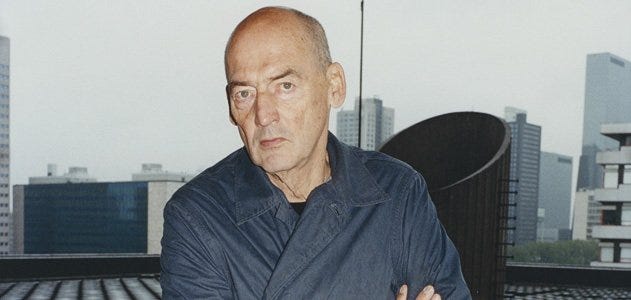

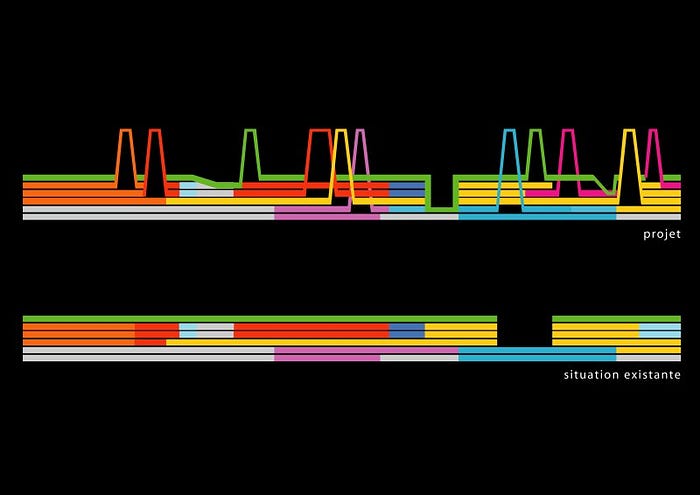

Rem Koolhaas, the Pritzker Prize-winning Dutch architect, theorist, and provocateur, spoke with Mohsen Mostafavi, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, in the closing keynote for the 2016 AIA convention.

Koolhaas, who founded the acclaimed architecture firm OMA, candidly spoke about the professions’ shortcomings, how it could adapt to the changing social and technical climates of today, and how its rare ability to do ‘ballet-like stretches’ holds the key to the future.

Rem Koolhaas: “Architecture stands with one leg in a world that’s 3,000 years old and another leg in the 21st century. This almost ballet-like stretch makes our profession surprisingly deep. You could say that we’re the last profession that has a memory, or the last profession whose roots go back 3,000 years and still demonstrates the relevance of those long roads today. Initially, I thought we were actually misplaced to deal with the present, but what we offer the present is memory.”

Read on Co.Design: http://www.fastcodesign.com/3060135/innovation-by-design/rem-koolhaas-architecture-has-a-serious-problem-today.

In 2012, Smithsonian asked why Rem Koolhaas is the world’s most controversial architect. A few quotes …

“Koolhaas’ habit of shaking up established conventions has made him one of the most influential architects of his generation. A disproportionate number of the profession’s rising stars, including Winy Maas of the Dutch firm MVRDV and Bjarke Ingels of the Copenhagen-based BIG, did stints in his office. Architects dig through his books looking for ideas; students all over the world emulate him. The attraction lies, in part, in his ability to keep us off balance. Unlike other architects of his stature, such as Frank Gehry or Zaha Hadid, who have continued to refine their singular aesthetic visions over long careers, Koolhaas works like a conceptual artist — able to draw on a seemingly endless reservoir of ideas. Yet Koolhaas’ most provocative — and in many ways least understood — contribution to the cultural landscape is as an urban thinker.”

“Running against the current and running with the current. Sometimes running with the current is underestimated. The acceptance of certain realities doesn’t preclude idealism. It can lead to certain breakthroughs.” — Rem Koolhaas

“More troubling perhaps to Koolhaas, the architectural climate has become more conservative, and hence more resistant to experimental work. (Witness the recent success of architects like David Chipperfield, whose minimalist aesthetic has been praised for its comforting simplicity.) As someone who has worked closely with Koolhaas put it to me: ‘I don’t think Rem always understands how threatening his projects are. The idea of proposing to construct villages in urban Hong Kong is very scary for the Chinese — it is exactly what they are running away from.’ Yet Koolhaas has always sought to locate the beauty in places that others might regard as so much urban debris, and by doing so he seems to be encouraging us to remain more open to the other. His ideal city, to borrow words he once used to describe the West Kowloon project, seems to be a place that is ‘all things to all people’.”

In fact Koolhaas’ urbanism, one could say, exists at the tipping point between the world as it is and the world as we imagine it.

Read on Smithsonian: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/why-is-rem-koolhaas-the-worlds-most-controversial-architect-18254921/?all.

Tertius the Brewer, Junius the Cooper and Julius Classicus — the up-and-coming military commander who would turn traitor against Rome a decade later — have sprung back to life from the first decade of Roman London, their names, along with the first reference to London itself, miraculously preserved on writing tablets in a sodden hole in the heart of the City. The wooden tablets, preserving the faint marks of the words written on bees wax with a metal stylus almost 2,000 years ago, are the oldest handwritten documents ever found in the UK.

“I ask you by bread and salt that you send as soon as possible the 26 denarii in victoriati and the ten denarii of Paterio.” — anonymous (dated to AD62–70).

Read on The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jun/01/tablets-unearthed-city-glimpse-roman-london-bloomberg.

“The beauty of architecture is that it’s a leap of faith, but a very laborious leap of faith.” — Rem Koolhaas