Random finds (2016, week 24) — On quantum leadership, the power of constraints, and happy daydreaming

Every Friday, I run through my tweets to select a few observations and insights that have kept me thinking over the last week.

Quantum leadership

“As the founder of the company, I didn’t want us to fail. As a human being, I wanted affirmation that my idea was a good one. As a ‘quantum manager,’ I bit my tongue. Ultimately, I didn’t engage in the brainstorming process because I knew my team would latch onto anything I offered. Instead, I just told them what winning would look like: a 300% increase in user engagement seemed like a lofty goal, but I pitched it anyways. A few days later, my team returned with a solution that I could never have imagined, and the results were stunning.”

In The Principles of Quantum Team Management, James Everingham, who is Instagram’s Head of Engineering, explains why setting up your team the way you would set up a machine can give you a ton of leverage. That is, as long as you realize how complicated and unpredictable the people in that machine can be. “This is where quantum mechanics (and my term ‘quantum leadership’) comes into play,” Everingham writes. “As a discipline, it makes the unpredictable understandable. Similarly, by applying these quantum principles to management, you can find solutions to your team’s seemingly unsolvable problems.”

According to Everingham, most managers try to add value by sharing their ideas, thoughts, possible solutions, and so on. By doing so, they dramatically reduce the number of possible outcomes. Instead, if you simply outline the problem and what success looks like, e.g. increasing revenue by 100%, all paths to success are still possible, including those you haven’t thought of yourself. It’s very likely that someone on your team will think of a better solution, but as soon as you say what you think, everyone gets a whole lot less creative.

“I used to make this mistake a lot when I was a junior manager. I would give my team ideas to get them started, and as soon as I thought they were headed toward failure or a dead end, I’d stop them and say something to turn them around. It seemed like it was in everyone’s best interests to avoid the wrong solution, but a mentor of mine told me that my team would never get better if I didn’t let them learn from failure. When I finally loosened my grip and let things go, I realized that my ideas were actually only right half of the time. The other half, my team’s ideas were far better than mine. I’d been an idiot for 10 years of my career, I realized.”

Being a good manager is about enabling as many different paths forward as possible for as long as possible.

Successful quantum managers follow five principles.

They manage to multiple ‘states’ as opposed to singular outcomes. Effective quantum managers do everything in their power to organize teams strategically and then step back. By avoiding prescribed paths, agreeing to outcomes, and providing each team with equal parts space and guidance, quantum managers set up their team for infinite success.

They are hyper-aware of the observer effect. The art of quantum management lies in discovering methods for gathering information about the unobservable, and preparing for all forms of success and failure while keeping the box closed.

They know when to open the box. Use the time you might have spent generating your own ideas for how to solve problems — or generally stressing your team out with micromanagement — to devise non-judgmental, thought-provoking questions.

They understand and create strategic entanglements. Successful quantum managers entangle and motivate positive traits on their teams, such as accountability, empathy and togetherness, to accelerate progress and increase quality.

They embrace the challenge of self-observation. Seeking constant feedback from those outside our ‘quantum management box’, like from our peers managing other segments of the business, allows us to stretch and grow without limiting our own outcomes.

By not offering our own ideas, we enable our teams to create a better one. And by not suggesting a destination, we might end up somewhere extraordinary — a place we didn’t even know we were going.

More on teams…

- Walter Isaacson, President and CEO of the Aspen Institute, a nonpartisan educational and policy studies organization based in Washington, D.C., and author of the authorized biography Steve Jobs, discusses how Jobs may have had a prickly personality, but his ability to build loyal and innovative teams was one of his greater talents. (BigThink)

- Wicked-Problem Solvers, by Amy C. Edmondson, on how cross-industry team can bring radical innovation. The question is how to build and run them. (Harvard Business Review)

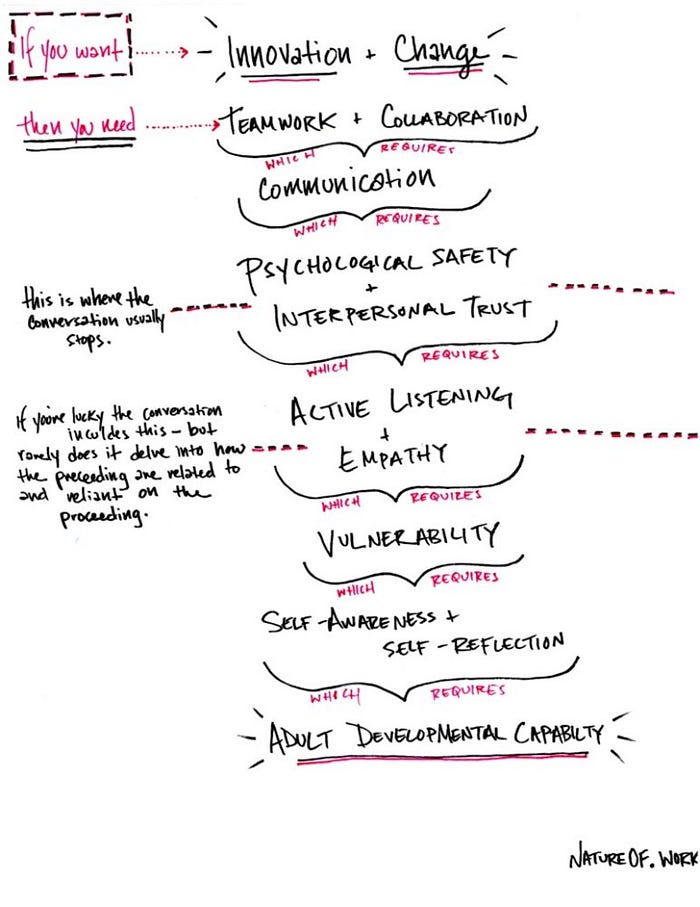

- Generative Team Design. Innovation, Psychological Safety, and Empathy, by Dara Blumenthal, PhD and Nathan Snyder.

- Google’s Unwritten Rule for Team Collaboration, by Paul Berkovic.

- And finally, Steve Jobs brainstorming with the NeXT team. A glimpse of his vision, aspirations and managerial approach (1985). Probably not the greatest example of ‘quantum leadership’ …

The power of constraints

“Nearly every science-fiction novel seems to agree on one thing: in the future, work will be indistinguishable from art. Such wide agreement suggests that work is far more than a means of income generation. Even in a robot servant utopia, with all our practical needs taken care of, human work will still have a purpose. To find or make meaning, to know thyself, to create beauty or value in the world. Productivity is helpful in these deeper pursuits because the fundamental questions it seeks to answer — how order arises from disorder, complexity from randomness, and ends from means — are the very same questions essential to understanding sentience, life, the universe, and everything.”

In Meta-Skills, Macro-Laws, and the Power of Constraints, Tiago Forte explores, what he believes are the two pillars of self-knowledge when it comes to productivity: meta-skills and macro-laws. “The ultimate purpose of productivity and self-improvement frameworks is thus to help you gain self-knowledge through the medium of practical lessons in getting shit done,” he writes. According to Forte, meta-skills are the skills you need to leverage other skills. They are the tools of survival, helping you stay alive long enough to find shelter, food, and water, while macro-laws are the map you’ll need to find your way to more interesting places.

There is a common thread uniting both meta-skills and macro-laws: the power of constraints. Meta-skills are constraints on how you work, to better leverage your knowledge, intelligence, time, people, and other resources. Macro-laws are constraints on what you work on, limiting your search space to a direction most likely to be fruitful.

“But there’s just one problem,” Forte writes. “How can something that is literally ‘not there’ have any effect on the material world? How can constraints have power?”

In his book Incomplete Nature, the American neuroanthropologist Terrence Deacon, who is currently Professor of Anthropology and member of the Cognitive Science faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, proposes an answer. He argues that there is a problem with how we think about emergent, complex systems (like productivity, consciousness, and life): we imagine each as ‘more than the sum of its parts.’ This has become practically the definition of emergence: life is more than just chemistry, information more than just bits, and consciousness more than just neurons. But we run into problems when we try to define what this ‘something more’ actually is. But Deacon makes a daring argument that helps explain how meta-skills and macro-laws work. He argues that emergent phenomena are not more than the sum of their parts. Instead, they are less than the sum of their parts. In other words, emergence is defined by what is not there — by constraints.

Deconstruct complexity into its components, and you dissolve the very relationships that give rise to it, and are left with nothing.

“This seems, in fact, to be the nature of all sorts of things we have trouble explaining through simple causality — they exist primarily in relation to something not there,” Forte explains. “Purpose refers to a future goal that doesn’t yet exist. Function relates to an external mapping that is likewise immaterial. Even Information seems to be distinguishable from noise only by its being ‘about’ something else (its intentionality, in philosophical terms). This could explain why reductionist analyses don’t work in explaining consciousness, or any other emergent phenomenon: what doesn’t exist has no parts. Deconstruct the experience of mind into its components, and you dissolve the very relationships that give rise to it, and are left with nothing.”

“What matters is not even relationships between parts, but relationships between constraints,” Forte continues. “Think of a rug woven with many threads into intricate patterns. The rug is ‘defined’ by the self-entanglement and reciprocal constraints that the threads impose on each other. The ways they probabilistically shape each others’ possibilities for change. Nothing magical or mysterious is added to the threads to make it a rug, yet you could individually replace each thread and still have the same rug. It is the connectional geometry of the system, the ways that constraints interact at different levels, that produces the emergent rug. This geometry has great causal power, but is not something material. It influences the probabilities of how things will change, by declaring how they won’t change.”

We think that increasing complexity must mean ‘adding more and more of something.’ As bacteria become animals become humans (or data becomes information becomes wisdom), we look everywhere for that ‘something added,’ yet turn up empty-handed. According to Deacon, however, work creates constraints (a beaver building a dam to channel water), but constraints also create work (a dam using channeled water to produce electricity). Round and round they go, constraints generating work to create more constraints to generate more work.

What sets us apart from machines is the power of our intention.

“Is there any better definition of productivity?,” Forte asks. “We learn meta-skills to perform higher-leverage work, but the best source of leverage is creating new constraints — new macro-laws. These macro-laws channel our energy more efficiently, giving us the surplus resources to acquire yet more skills. Improving one’s productivity is not a self-organizing process, but a self-simplifying one.”

This theory provides a clue to understanding what sets human work apart from machine work. After all, machines are perfectly capable of acquiring both skills, and following laws. What sets us apart is the power of our intention.

A bit more …

In a recent paper titled Ode to Positive Constructive Daydreaming, published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, writer Rebecca McMillan and NYU cognitive psychologist Scott Kaufman, author of Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined, revisit Jerome L. Singer’s groundbreaking research into daydreaming to deliver new insights into how the first style of Singer’s mind-wandering, rather than robbing us of happiness, plays an essential, empowering role in daily life and creativity. One of the most fascinating aspects the authors explore is the seeming paradox of the high costs of daydreaming, which prevents us from wholly inhabiting the present moment, and the astounding frequency with which we engage in it.

“Our human condition is such that we are forever in the situation of deciding how much attention to give to self-generated thought and how much to information from the external social or physical environment.” — Jerome L. Singer

“Right from the start, Singer’s research produced evidence suggesting that daydreaming, imagination, and fantasy are essential elements of a healthy, satisfying mental life. His early research included studies looking at delayed gratification and the interaction of imagination and waiting ability in young children. In another early study presented evidence of correlation between daydreaming frequency, measures of creativity, and storytelling activity. […] Singer explored the relationship between daydreaming, personality, divergent thought, creativity, planning, problem solving, associational fluency, curiosity, attention, and distractibility. Singer noted that daydreaming can reinforce and enhance social skills, offer relief from boredom, provide opportunities for rehearsal and constructive planning, and provide an ongoing source of pleasure. In later work, Singer describes those who engage in positive constructive daydreaming as ‘happy daydreamers’ who enjoy fantasy, vivid imagery, the use of daydreaming for future planning, and possess abundant interpersonal curiosity.”

Read on Brainpickings: https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/10/09/mind-wandering-and-creativity.

More on daydreaming and mind-wandering in Random finds (2016, week 18).

“There are many moments throughout my average day that, lacking print reading material in a previous era, were once occupied by thinking or observing my surroundings: walking or waiting somewhere, riding the subway, lying in bed unable to sleep or before mustering the energy to get up. Now, though, I often find myself in these situations picking up my phone to check a notification, browse and read the internet, text, use an app or listen to audio (or, on rare occasions, engage in an old-fashioned ‘telephone call’). The last remaining place I’m guaranteed to be alone with my thoughts is in the shower,” Teddy Wayne writes in The End of Reflection. He also cites Nicholas Carr, who wrote a book about what the internet is doing to our brains, The Shallows:

“We’ve adopted the Google ideal of the mind, which is that you have a question that you can answer quickly: close-ended, well-defined questions. Lost in that conception is that there’s also this open-ended way of thinking where you’re not always trying to answer a question. You’re trying to go where that thought leads you. As a society, we’re saying that that way of thinking isn’t as important anymore. It’s viewed as inefficient.”

Read on New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/12/fashion/internet-technology-phones-introspection.html?_r=1&referer=.

As many have done before, also Cal Newport argues that the internet has had a corrosive effect on our ability to concentrate. “Spend enough time in a state of frenetic shallowness and you permanently reduce your capacity to perform deep work,” he warns in his book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World.

Nicholas Carr complained that even deep reading was becoming a struggle for him and an entire culture in his famously alarming 2008 essay in The Atlantic, Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. One study found that workers are able to spend only 11 minutes on a task before being interrupted. The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress by Gloria Mark of the University of California, Irvine, detected no difference in the quality of work by those getting interrupted, and the study suggested that “people compensate for interruptions by working faster.” But interruptions came at a price: “experiencing more stress, higher frustration, time pressure and effort.”

In fact, there is a growing need for deep work, and that is new, Newport claims. But there is much in the way jobs are organized today that is at odds with producing high-quality results. Multitasking can be a drain on concentration, and also even moving among projects comes with a built-in inefficiency. Not many organizations recognize this need, though. With some studies showing employees spending 50% of their time on email, “half of your time is already gone on basic coordination of activities. My guess is you are not getting time to focus. There are organizations that are good creative cultures, but part of the reason there is a receptive audience for Cal’s book is because this is a problem in most work places,” says Adam Grant, a professor of psychology at Wharton’s Management Department, and author of Originals about how to champion new ideas and fight groupthink.

Read on Knowledge@Wharton: http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/can-deep-work-really-work.

In The Filter Bubble, Rhoda Marsden explores the question whether digital technology saps our creativity and leads to cultural homogeneity.

Last year, Ravi Mehta and Meng Zhu published a study in the Journal of Consumer Research on the link between abundance and creativity over a series of six experiments. “What we found,” said Mehta, “is that abundant resources may have a negative effect on creativity. When you have fewer resources, you use them more creatively.”

But the digital world is curious in this respect. Yes, technology encourages us to create by restricting the options available, but it tries desperately to guarantee pleasant results with minimum effort. We’re discouraged from pushing our creative boundaries. As a result, the likelihood of producing something new, surprising or valuable is diminished.

Creativity is a process, not a product: we might only be able to describe it in terms of the results, but it’s the mental process we need to understand.

Read on TheLong+Short: http://thelongandshort.org/creativity/is-technology-stifling-creativity.

According to Alex Cocoas in Design for the One Percent, contemporary architecture is more interested in mega projects for elites than improving ordinary people’s lives.

We need less Gehrys, less Hadids, less bloated egotecture. We need more shit, more beautiful shit for the rest of us.

“Ever since Frank Gehry designed the Guggenheim Museum in post-industrial Bilbao, instantly turning the city into a tourist destination, municipalities around the world have been shelling out hundreds of millions of dollars in public money for civic and cultural buildings. Boosters claim these cultural institutions will attract more transnational capital flows, more real estate investment, more tourists, more ‘innovation hubs’ — the buzzword soup is bottomless. These projects don’t address, however, the structural problems — declining industry, wages, and state investment — that precipitated their supposed necessity. They don’t aim to ‘revitalize’ the city, they aim to globalize it.”

Read on Jacobin: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/06/zaha-hadid-architecture-gentrification-design-housing-gehry-urbanism.

And on De Zeen how visiting Zaha Hadid’s Vitra Fire Station was an eye-opening experience for Danish architect Bjarke Ingels: http://www.dezeen.com/2016/06/19/video-interview-bjarke-ingels-zaha-hadid-vitra-fire-station-eye-opening-experience-movie.

Can anything be art? Why are Jackson Pollock’s splattered canvases high art, while a pair of glasses, left on the floor of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art by two high school students, is not? The key lies in curatorship, according to art historian Amy E. Herman.

“Curators ground individual works of art within a collection and aim to make the artwork more accessible to broader audiences. Their choices about which pieces to include and how to display them affords the viewer a template for looking at, and engaging with, the artwork, providing context with which to view, consider, question, and form opinions about what they see.”

“Objects in museums are never scattered about at random. Rather, they are installed after a painstaking process of reflection. While visitors may not always be able to see the work that has gone into an exhibit, curators are careful to make them cohere according to form, theme, context, and chronology, among other attributes. In this way, museums aim to intellectually stimulate their visitors and to provide an immersive sensory experience that offers a crucial respite from the wired world.”

The glasses on the floor certainly inspired viewers to look twice, and perhaps even to ask questions, but they were completely without context or connection in that particular museum. The truth is that just because people are looking at something doesn’t make it deep. The glasses were an amusing spectacle, but not a work of art.

Read on Quartz: http://qz.com/703590/can-anything-be-art-an-art-historian-explains-why-not.

“The mainstream is a current too strong to think in.” — Paul Shepherd