Random finds (2016, week 25) — On the secret of taste, debunking business philosophy, and the virtues of an idle mind

Every Friday, I run through my tweets to select a few observations and insights that have kept me thinking over the last week.

The secret of taste

How does a song we dislike at first hearing become a favourite? And when we try to look different, how come we end up looking like everyone else? These are the kind of questions Tom Vanderbilt, an American journalist, blogger, and author of You May Also Like. Taste in an Age of Endless Choice, explores in his long read The secret of taste: why we like what we like.

“Even when we look back and see how much our tastes have changed, the idea that we will change equally in the future seems to confound us,” Vanderbilt writes. The psychologist Timothy Wilson has identified the illusion that for many, the present is a “watershed moment at which they have finally become the person they will be for the rest of their lives”.

One of the reasons we cannot predict our future preferences is one of the things that makes those very preferences change: novelty. In the science of taste and preferences, novelty is a rather elusive phenomenon. On the one hand, we crave novelty, which defines a field such as fashion. Or, in the words Saks Fifth Avenue’s president Ronald Frasch: “The first thing the customer asks when they come into the store is, ‘What’s new?’ They don’t want to know what was; they want to know what is.” How strong is this impulse? “We will sell 60% of what we’re going to sell the first four weeks the goods are on the floor.”

But at the same time, we adore familiarity. There are many who believe we like what we are used to. And yet if this were strictly true, nothing would ever change. “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” as Steve Jobs put it. And even then, they still might not want it, like Apple’s ill-fated Newton PDA device that was, as Wired described it, “a completely new category of device running an entirely new architecture housed in a form factor that represented a completely new and bold design language”.

So, novelty or familiarity? As is often the case, the answer lies somewhere in between. Industrial designer Raymond Loewy sensed this optimum in what he termed the ‘MAYA stage.’ for ‘most advanced, yet acceptable.’ This was the moment in a product design cycle when, Loewy argued, “resistance to the unfamiliar reaches the threshold of a shock-zone and resistance to buying sets in”.

We like the new as long as it reminds us in some way of the old.

There is this fascinating phenomenon called ‘skeuomorphs.’ Compounded from the Greek skéuos, σκεῦος (container or tool), and morphḗ, μορφή (shape), the word has been used to describe objects that retains ornamental design cues that were necessary in the original. In other words: details that are not included because of their functionality, but either for their social desirability or psychological comforts. We make new innovations fit into the present cultural ecosystem by using elements we already know. We design the future by referring to the past.

Katherine Hayles, author of the book How We Became Posthuman, describes the phenomenon the following way:

“A skeumorph is a design feature that is no longer functional in itself but that refers back to a feature that was functional at an earlier time. Skeuomorphs visibly testify to the social or psychological necessity for innovation to be tempered by replication. Like anachronisms, their pe-jorative first cousins, skeuomorphs are not unusual. On the contrary, they are so deeply characteristic of the evolution of concepts and artifacts that it takes a great deal of conscious effort to avoid them.”

The act of using familiar concepts or items to make new technologies less strange or confusing shows our ingenious way of moving the ‘familiarity’ line. It’s one of our ways of constantly moving forward by making innovations seem less disruptive.

[If you want to read more about skeuomorphism, I recommend Laurens Martens’ post on MindMedley, Skeuomorphs: Innovative Nostalgia.]

Back to Vanderbilt and taste…

Because we cannot see past our inherent resistance to the unfamiliar, it is hard to anticipate how much our tastes will change. Or how much we will change when we do and how each change will open the door to another change. We forget just how fleeting even the most jarring novelty can be. “When you had your first sip of beer (or whisky), you probably did not slap your knee and exclaim, ‘Where has this been all my life?’ It was, ‘People like this?’,” Vanderbilt writes. Looking back though, we often find it hard to believe we did not like something we now do.

“It now seems impossible to imagine, a few decades ago, the scandal provoked by the now widely cherished Sydney Opera House [now on UNESCO’s World Heritage List for its outstanding universal value]. The Danish architect, Jørn Utzon, was practically driven from the country, his name went unuttered at the opening ceremony, the sense of national scandal was palpable towards this harbourside monstrosity. Not only did the building not fit the traditional form of an opera house; it did not fit the traditional form of a building. It was as foreign as its architect.”

Until Utzon, nobody had ever thought an opera house could like that. However, a few decades from now, someone will inevitably look with dread upon a new building and say, “The Sydney Opera House, now there’s a building. Why can’t we build things like that any more?”

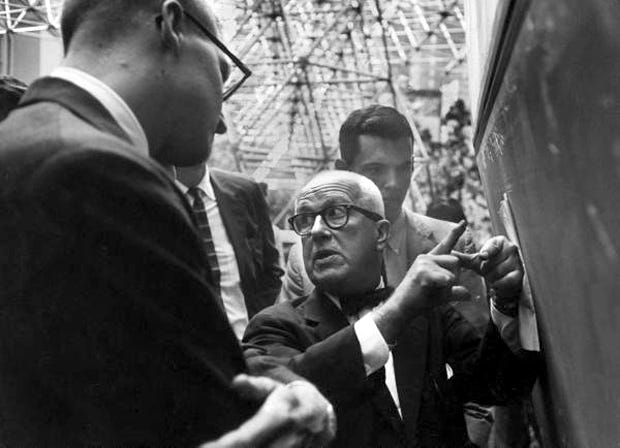

[The Guardian recently published an interesting article about Ove Arup, the Danish British engineer and founder of the Arup Group, who was the structural brain behind Sydney Opera House and the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Three decades after his death, Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design at the V&A, celebrates the 20th century’s most influential engineer.]

Our taste is “a kind of perpetual motion machine,” driven by the oscillations of novelty and familiarity. But it is also driven by the subtle movements of people trying to be like each other and people trying to be different from each other. “There is a second-guessing kind of struggle here, not unknown to […] readers familiar with Dr Seuss’ Sneetches, the mythical star-adorned creatures who suddenly ditch their decorations when they discover their rival plain-bellied counterparts ‘have stars upon tears’,” Vanderbilt writes.

The French socialist Gabriel Tarde wrote, in his 1890 book The Laws of Imitation, that that people are social beings. They are essentially imitative. This, what is known as ‘social learning’, is an evolutionary adaptive strategy that helps us to survive, even prosper. No other species are better social learners than humans. None continue to build upon their knowledge through successive generations. It is the sum of this social learning — culture — what makes humans so unique, and so uniquely successful.

As the anthropologist Joseph Henrich notes, humans have foraged in the Arctic, harvested crops in the tropics, and lived pastorally in deserts. This is not because we were meant to, but because we learned to.

In their book Not by Genes Alone, the anthropologists Robert Boyd and Peter Richardson argue that people imitate, and culture becomes adaptive, because learning from others is more efficient than trying everything out on your own through costly and time-consuming trial and error.

But if social learning is so easy and efficient, it raises the question of why anyone does anything different to begin with. “Boyd and Richardson suggest there is an optimal balance between social and individual learning in any group,” Vanderbilt explains. “Too many social learners, and the ability to innovate is lost: people know how to catch that one fish because they learned it, but what happens when that fish dies out? Too few social learners, and people might be so busy trying to learn things on their own that the society does not thrive; while people were busily inventing their own better bow and arrow, someone forgot to actually get food.”

Perhaps some ingrained sense of the evolutionary utility of this differentiation explains why humans are so torn between wanting to belong to a group and wanting to be distinct individuals. Most of us want to be different, but not too different. “If all we did was conform, there would be no taste; nor would there be taste if no one conformed. We try to select the right-sized group or, if the group is too large, we choose a subgroup. Be not just a Democrat but a centrist Democrat. Do not just like the Beatles; be a fan of John’s.”

Debunking modern business philosophy

In 2006, Matthew Stewart, an American philosopher and author, wrote in an article in The Atlantic, The Management Myth, that most of management theory is inane. “If you want to succeed in business, don’t get an MBA. Study philosophy instead.”

“During the seven years that I worked as a management consultant, I spent a lot of time trying to look older than I was. I became pretty good at furrowing my brow and putting on somber expressions. Those who saw through my disguise assumed I made up for my youth with a fabulous education in management. They were wrong about that. I don’t have an MBA. I have a doctoral degree in philosophy — nineteenth-century German philosophy, to be precise. Before I took a job telling managers of large corporations things that they arguably should have known already, my work experience was limited to part-time gigs tutoring surly undergraduates in the ways of Hegel and Nietzsche and to a handful of summer jobs, mostly in the less appetizing ends of the fast-food industry.”

But, as anyone who has studied Aristotle will know, ‘values’ aren’t something you bump into from time to time during the course of a business career. All of business is about values, all of the time.

“The strange thing about my utter lack of education in management was that it didn’t seem to matter. As a principal and founding partner of a consulting firm that eventually grew to 600 employees, I interviewed, hired, and worked alongside hundreds of business-school graduates, and the impression I formed of the MBA. experience was that it involved taking two years out of your life and going deeply into debt, all for the sake of learning how to keep a straight face while using phrases like ‘out-of-the-box thinking,’ ‘win-win situation,’ and ‘core competencies.’ When it came to picking teammates, I generally held out higher hopes for those individuals who had used their university years to learn about something other than business administration.”

The idea that philosophy is an inherently academic pursuit is a recent and diabolical invention. Non of history’s great philosophers — Epicurus, Descartes, Spinoza, Locke, Hume, Nietzsche — were university professors. “If any were to come to life and witness what has happened to their discipline, I think they’d run for the hills,” Stewart writes. “Still, you go to war with the philosophers you have, as they say, not the ones in the hills. And since I’m counting on them to seize the commanding heights of the global economy, let me indulge in some management advice for today’s academic philosophers …”

Expand the domain of your analysis. Why so many studies of Wittgenstein and none of Taylor, the man who invented the social class that now rules the world?

Hire people with greater diversity of experience. And no, that does not mean taking someone from the University of Hawaii. You are building a network — a team of like-minded individuals who together can change the world.

Remember the three Cs: Communication, Communication, Communication. Philosophers (other than those who have succumbed to the Heideggerian virus) start with a substantial competitive advantage over the PowerPoint crowd. But that’s no reason to slack off. Remember Plato: it’s all about dialogue!

“With this simple three-point program (or was it four?) philosophers will soon reclaim their rightful place as the educators of management. Of course, I will be charging for implementation.”

The virtues of an idle mind

“Recently, I discovered how much we overlook, not just about the world, but also about the full potential of our inner life, when our mind is cluttered. In a study published in this month’s Psychological Science, the graduate student Shira Baror and I demonstrate that the capacity for original and creative thinking is markedly stymied by stray thoughts, obsessive ruminations and other forms of ‘mental load’,” Moshe Bar, the director of the Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center at Bar-Ilan University and a professor at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, writes in Think Less, Think Better.

Many psychologists assume that the mind, left to its own devices, is inclined to follow a well-worn path of familiar associations. But Baror and Bar’s findings suggest that innovative thinking, not routine ideation, is our default cognitive mode when our minds are clear. In general, they say, there is “a tension in our brains between exploration and exploitation. When we are exploratory, we attend to things with a wide scope, curious and desiring to learn. Other times, we rely on, or ‘exploit,’ what we already know, leaning on our expectations, trusting the comfort of a predictable environment. We tend to be more exploratory when traveling to a new country, whereas we are more inclined toward exploitation when returning home after a hard day at work.”

Honing an ability to unburden the load on your mind can bring with it a wonderfully magnified experience of the world.

“Much of our lives are spent somewhere between those extremes. There are functional benefits to both modes: If we were not exploratory, we would never have ventured out of the caves; if we did not exploit the certainty of the familiar, we would have taken too many risks and gone extinct. But there needs to be a healthy balance. Our study suggests that your internal exploration is too often diminished by an overly occupied mind, much as is the case with your experience of your external environment.”

In The end of Reflection, Teddy Wayne writes: “There are many moments throughout my average day that, lacking print reading material in a previous era, were once occupied by thinking or observing my surroundings: walking or waiting somewhere, riding the subway, lying in bed unable to sleep or before mustering the energy to get up. Now, though, I often find myself in these situations picking up my phone to check a notification, browse and read the internet, text, use an app or listen to audio (or, on rare occasions, engage in an old-fashioned ‘telephone call’). The last remaining place I’m guaranteed to be alone with my thoughts is in the shower.”

But as Baror and Bar’s findings make clear, unburdening the load on your mind can bring with it a wonderfully magnified experience of the world, and of your own mind. It’s time we start celebrating the virtues of an idle mind.

More on mind-wandering, daydreaming and mindfulness in Random thoughts — An exploration into our wandering minds.

A bit more …

“Questions trigger ideas, solutions and results,” Thomas Oppong writes in If You Can Ask The Right Questions, You Can Get Anything You Want.

“It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.” — Eugene Ionesco

“Some of the most creative and innovative companies of our time are better at asking exceptional questions that spark creativity and allow people to take things a step further to find amazing ideas to solve everyday problems. They are insanely good at asking questions.”

Read on Medium: https://medium.com/life-learning/if-you-can-ask-the-righ-questions-you-can-get-anything-you-want-c109c1bf7314#.yg20rr6dy.

According to Lisa Baird, a former principal designer at IDEO, in Why High-Skilled Freelancers Are Leaving Corporate Life Behind, in some industries, there’s now one freelance ‘comprehensivist’ where there used to be a team of specialists.

“Buckminster Fuller might have called someone like Nicolette Hayes [a visual and interactive designer at Stamen] a ‘comprehensivist’ — the opposite of a specialist. According to constructivist psychologist Spencer McWilliams, ‘Fuller was highly critical of disciplinary specialization, believing that it was originally instituted to support the interests of a power structure and keep intelligent individuals from knowing too much’.”

The rise of comprehensivists in some sectors is coinciding with the broader gig economy trend, Baird writes. Multi-skilled knowledge workers are increasingly able to ply their trade to a range of bidders on their own terms. Project-oriented fields like design and journalism have seen this coming for some time, in part because the deadlines they operate on make for easily definable gigs. But more and more fields formerly thought of as ‘non-creative’ are adopting creative processes, making their work more easily chunkable as well. As CEO of IDEO Tim Brown remarked in a recent IDEO U webcast, “The sign of an organization becoming more creative is the move from processes to projects — projects are inherently creative acts.

Read on Fast Company: http://www.fastcompany.com/3059898/the-future-of-work/how-high-skilled-freelancers-are-changing-the-rules-recruiting.

Founders Fund has launched a new mini series, called Anatomy of Next.

“In Anatomy of Next we’re going to explore five technologies most popularly feared in dystopia: nuclear science, synthetic biology, robotic automation, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality. We’re going to bring in experts from our community to discuss the real dangers concerning each of the technologies, and to troubleshoot strategies around them. Then we’re going to tell a different kind of story. Because imagine a world of unlimited energy. Because imagine a world of biological self-determination, of perfect health, and of the end of aging. Because imagine a world where the bounds of our reality are limited only by the extent of our imagination.”

Read and listen on Founders Fund: http://foundersfund.com/2016/06/thought-thoughts-future.

Scott Barry Kaufman, scientific director of the Imagination Institute and a researcher and lecturer in the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, explores whether you can be social and introspective.

“The fundamental human needs for connection and reflection enrich our lives, and infuse it with meaning and growth. However, we often treat the two as though they were on a seesaw: the more you have one in your life, the less you have the other. For instance, we often talk as though the more reflective you are as a person, the less social you are, or the more social you are, the less you engage in introspection. But are these really diametrically opposed ways of being, or instead, are they both on their own, independent seesaws, in great harmony with each other?”

So, Scott Barry Kaufman — “the uber-nerd that I am” — analyzed a preexisting dataset he had sitting on my computer. His conclusion: “It’s clear: Solitude and introspection can lead to a life full of connection, creativity, and meaning.”

Read on Scientific American: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautiful-minds/can-you-be-social-and-introspective/?WT.mc_id=SA_TW_MB_BLOG.

According to Monocle’s website, their new book, How to Make a Nation: A Monocle Guide, “explores all the elements you need to make a happy, vibrant and successful country. From designing a better parliament to choosing a flag, creating social capital to taking care of our young and old, this is a book about the small — and big — things that can make our nations work better for everyone who calls them home.”

But Mark O’Connell, who reviewed How to Make a Nation for TheLong+Short, writes: “Monocle’s version of the nation state is not a political entity, the result of ideological victories and defeats, but a lifestyle brand.”

“There is a lot to be said for soft power, but the idea that it can be considered in isolation from hard power is a delusion. If you’re going to devote four pages to the design of passport covers and banknotes, you should at least acknowledge that, say, homelessness exists, and that it exists for complex but nonetheless concrete social and political reasons. If you’re going to speak with any authority about how the world should be, you should at least recognise how it actually is, and why it might be that way.”

Still, it’s nice to have…

Read on TheLong+Short: http://thelongandshort.org/society/how-to-make-a-tasteful-nation.

In De Zeen, architect Rem Koolhaas speaks out against a Brexit. According to him, Leave campaigners are fighting for an England that doesn’t exist.

“Britain is a modern nation, the origin of the industrial revolution, the former centre of a global empire and, largely as a consequence, currently home to a global community. More than any other European country, Britain is multicultural. A retreat within the confines of its own borders is not only anti-modern, but ultimately un-British.”

“Discovery, like surprise, favors the well-prepared mind.” — Jerome Bruner