Random finds (2017, week 7) — On cyborgs and a world without consciousness, faux futurists, and the age of rudeness

“The four characteristics of humanism are curiosity, a free mind, belief in good taste, and belief in the human race.” — E.M. Forster

Random finds is a weekly curation of my tweets and a reflection of my curiosity.

On cyborgs and a world without consciousness

During the recent World Government Summit in Dubai, Elon Musk warned that humans must become cyborgs if they are to stay relevant in a future dominated by artificial intelligence. He argued that as artificial intelligence becomes more sophisticated, it will lead to mass unemployment. “There will be fewer and fewer jobs that a robot can’t do better.” If humans want to continue to add value to the economy, they must augment their capabilities through a “merger of biological intelligence and machine intelligence.” If we fail to do this, we will risk becoming ‘house cats’ to artificial intelligence.

In Elon Musk says humans must become cyborgs to stay relevant. Is he right?, Olivia Solon, a freelance technology journalist, explores where the science ends and science fiction starts.

As it turns out, we are still a long way from Elon Musk’s vision of symbiosis between man and machine, Solon writes. Such a symbiosis would require a much more granular understanding of the brain network that goes beyond the basics of motor control to more complex cognitive faculties like language and metaphor.

Professor Panagiotis Artemiadis of Arizona State University is skeptical that the rise of AI will render humans irrelevant. “We’re building these machines to serve humans,” he told Solon.

“Miguel Nicolelis, who has built brain-controlled exoskeletons and a brain-to-brain interface that allowed a rat in the United States to use the senses of the other in Brazil, agrees. Humans won’t become irrelevant until machines can replicate the human brain — something Nicolelis believes isn’t possible,” Solon writes.

Contrary to what Musk and Singularity proponents like Ray Kurzweil say, Nicolelis argues that our brain is not computable because consciousness is the result of unpredictable, nonlinear interactions among billions of cells. Although Nicolelis acknowledges that digital automation will lead to serious unemployment among people who perform certain mundane functions that can be replicated by machines, he doesn’t believe this will make the human species become obsolete. Humans will retain ultimate control, even we can interface directly with machines, he believes.

“The idea that digital machines no matter how hyper-connected, how powerful, will one day surpass human capacity is total baloney.” — Miguel Nicolelis, neuroscientist

“A worry for Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist David Chalmers is creating a world devoid of consciousness,” Paul Ratner writes in Automation Nightmare. Chalmers sees the discussion of future superintelligences often presume that eventually AIs will become conscious. “But what if that kind of sci-fi possibility that we will create completely artificial humans is not going to come to fruition? Instead, we could be creating a world endowed with artificial intelligence but not actual consciousness,” he says.

“For me, that raising the possibility of a massive failure mode in the future, the possibility that we create human or super human level AGI and we’ve got a whole world populated by super human level AGIs, none of whom is conscious. And that would be a world, could potentially be a world of great intelligence, no consciousness, no subjective experience at all. Now, I think many many people, with a wide variety of views, take the view that basically subjective experience or consciousness is required in order to have any meaning or value in your life at all. So therefore, a world without consciousness could not possibly a positive outcome. Maybe it wouldn’t be a terribly negative outcome, it would just be a zero outcome, and among the worst possible outcomes.” (starting at 22:27)

Chalmers solution to this issue of an AI-run world without consciousness is to create a world of AIs with human-like consciousness.

“I mean, one thing we ought to at least consider doing there is making, given that we don’t understand consciousness, we don’t have a complete theory of consciousness, maybe we can be most confident about consciousness when it’s similar to the case that we know about the best, namely human human consciousness. So, therefore maybe there is an imperative to create human-like AGI in order that we can be maximally confident that there is going to be consciousness.” (starting at 23:51)

By making it our clear goal to fully recreate ourselves in all of our human characteristics, we may be able to avoid a soulless world of machines becoming our destiny. But as we don’t understand consciousness, perhaps this is a goal doomed to failure, Paul Ratner fears.

(video: During The Beneficial AI 2017 Conference, Elon Musk, Stuart Russell, Ray Kurzweil, Demis Hassabis, Sam Harris, Nick Bostrom, David Chalmers, Bart Selman, and Jaan Tallinn discussed, with Max Tegmark as moderator, what likely outcomes might be if we succeed in building human-level AGI, and also what we would like to happen.)

Fast Company met with Yuval Noah Harari, whose new book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, looks ahead and hazards a few guesses on what’s next for humanity.

According to Harari, there are two important questions for audiences from the tech world. First, does the tech world understand human society well enough to really appreciate what technological developments are going to do to humanity and the world? In many cases, the answer is no. The other big scientific question has to do with the human mind and consciousness. “We are making tremendous development in understanding the human brain and intelligence, but we are making comparatively little progress in understanding the mind and understanding consciousness.”

“So far, we don’t have any serious theory of human consciousness. The widespread assumption is that somehow the brain produces the mind, somehow millions of neurons fire signals at one another create or produce consciousness, but we have no idea how or why this happens. I’m afraid that in many cases, people in the tech world fail to understand that. They equate brain with mind, and equate intelligence with consciousness, even though they’re separate things.

In human beings, as with other mammals, consciousness and the mind often goes hand in hand, but that’s not the same thing. We know of other organisms that have intelligence but no consciousness (as far as we know) like trees. Intelligence is the ability to solve problems, and consciousness is the ability to feel things and have subjective experiences.”

Every technology can be the basis for very different social and political systems. You cannot just stop the march of technology — this is not an option — but you can influence the direction it is taking.

“The fact that we don’t understand the mind and consciousness also implies that there is absolutely no reason to expect computers or artificial intelligences to develop consciousness anytime soon. Since the beginning of the computer age, there has been immense development in computer intelligence but exactly zero development in computer consciousness.

Even the most sophisticated computer and AI software today, as far as we know, has zero consciousness — no feelings and no emotions whatsoever. And one of the dangers is that if we, and we are gaining the ability to manipulate the human body and the human brain, but we don’t understand the human mind, we won’t be able to foresee the consequences of these manipulations.”

On faux futurists

“Who cares what one eccentric startup founder [Rob Rhinehart, the founder of Soylent] believes the future will look like?,” Liz Alexander, a consulting futurist and co-founder of Leading Thought, asks in What Faux Futurists Cost The Rest Of Us.

First, because there is no shortage of entrepreneurs who double as amateur futurists, declaring to the rest of us what’s coming. Second, because the future they imagine reflects “a tiny elite’s wishful thinking,” not what most people need. And what more people need is a greater hand in shaping their own futures, Alexander writes.

But it isn’t news that Silicon Valley’s idea of the future is often out of sync with what makes most of us tick. “Last year, Singularity University’s Peter Diamandis projected that fully autonomous vehicles would hit roadways ‘well within five years.’ Yet, in study after study, most Americans across all age groups say they want to stay in the driver’s seat. Even if we know that cars will likely be safer under the control of AI, many of us actually like driving. Reason doesn’t always win out, people’s irrational preferences do.”

Predicting the future is big business, says Alexander. “Why merely satisfy a need, the Steve Jobs-ian logic goes, when you can create one that people didn’t know they had? Get ahead of a trend, and you stand to make gobs of money. Create a trend, and make gobs more.”

But isn’t it the function of every business to answer the following question with integrity: “What problem are we solving?”

With integrity because ‘Econ 101’ poses that question simply for the sake of identifying a target customer segment. Today’s world however, “begs us to think a lot harder and more urgently about collective problems in addition to consumer ones: climate change, the erosion of democratic principles, threats by stateless enemies. Want to make an impact on the future we’ll all have to live in? Want to really innovate? Start by asking ordinary people what they want tomorrow to look like, then work backward from there,” Alexander argues.

“People become more inclined to reject things when they feel all their options are bad,” as both Trump’s victory and the outcome of the Brexit referendum show. Alexander believes this is why the familiar outcry for greater diversity matters so much, especially right now. “Companies need to reflect the world they’re trying to reshape. When they do, they’re better at seeing humans as something more than math problems knowable through trend analysis.”

In reality, humans are complex and inefficient creatures. Sociable joy seekers who search for meaning in their lives and work. “Those things have always been trending. Lately, there’s a lot that threatens them, and that’s a problem that all the internet-connected coffee makers in the world can’t solve, but that real food-guzzling, car-driving people just might.”

A bit more …

“Society organizes itself very efficiently to punish, silence or disown truth-tellers. Rudeness, on the other hand, is often welcomed in the manner of a false god. Later still, regret at the punishment of the truth-teller can build into powerful feelings of worship, whereas rudeness will be disowned,” says Rachel Cusk in a thought-provoking and beautifully written essay in The New York Times Magazine, titled The Age of Rudeness— As the social contract frays, what does it mean to be polite?

“Are people rude because they are unhappy? Is rudeness like nakedness, a state deserving the tact and mercy of the clothed? If we are polite to rude people, perhaps we give them back their dignity; yet the obsessiveness of the rude presents certain challenges to the proponents of civilized behavior. It is an act of disinhibition: Like a narcotic, it offers a sensation of glorious release from jailers no one else can see.”

“In Sophocles’ play ‘Philoctetes,’ the man who suffers most is also the man with the most powerful weapon, an infallible bow that could be said to represent the concept of accuracy. The hardhearted Odysseus abandoned the wounded Philoctetes on an island, only to discover 10 years later that the Trojan War could not be won without Philoctetes’ bow. He returns to the island determined to get the bow by any means. For his part, Philoctetes has spent 10 years in almost unendurable pain: It is decreed that he cannot be healed other than by the physician Asclepius at Troy, yet he would rather die than help Odysseus by returning with him. Time has done nothing to break down the impasse: Philoctetes still can’t forgive Odysseus; Odysseus still can’t grasp the moral sensitivity of Philoctetes. It is for the third actor, Neoptolemus, a boy of pure heart, to resolve the standoff and bring an end to war and pain. Odysseus urges Neoptolemus to befriend Philoctetes in order to steal the bow, claiming it is for the greater good. Philoctetes, meanwhile, tells Neoptolemus the story of his dreadful sufferings and elicits his empathy and pity. In his dilemma, Neoptolemus realizes two things: that wrong is never justified by being carried out under orders, and that the bow is meaningless without Philoctetes himself. The moral power of individuality and the poetic power of suffering are the two indispensable components of truth. For his part, Neoptolemus might be said to represent the concept of good manners. In this drama, the expressive man and the rude man need each other, but without the man of manners, they will never be reconciled.”

“It strikes me that good manners would be the thing to aim for in the current situation. I have made a resolution, which is to be more polite. I don’t know what good it will do: This might be a dangerous time for politeness. It might involve sacrifices. It might involve turning the other cheek. A friend of mine says this is the beginning of the end of the global order: He says that in a couple of decades’ time, we’ll be eating rats and tulip bulbs, as people have done before in times of social collapse. I consider the role that good manners might play in the sphere of rat-eating, and it seems to me an important one. As one who has never been tested, who has never endured famine or war or extremism or even discrimination, and who therefore perhaps does not know whether she is true or false, brave or a coward, selfless or self-serving, righteous or misled, it would be good to have something to navigate by.”

When Carole Cadwalladr met Daniel Dennett on the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration, she asked him whether Dennett thinks we are already in a situation where the technology is too complicated even for the people who created it to understand it?

“That’s a worry and possibility,” according to Dennett. “I don’t think that point has been reached, but that point could be reached. What’s interesting is that philosophers for hundreds of years have talked about the limits of comprehension as if it was sort of like the sound barrier. There was this wall we just couldn’t get beyond and that was part of the tragic human condition. Now, we’re discovering a version of it, which, if it’s true is sort of true in a boring way. It’s not that there are any great mysteries, it’s just that the only way we can make progress is by division of labour and specialisation.”

“For example, the papers coming out of Cern with 500 authors, no one of whom understands the whole paper or the whole science behind it. This is just going to become more and more the meme. More and more, the unit of comprehension is going to be group comprehension, where you simply have to rely on a team of others because you can’t understand it all yourself. There was a time, I would say as recently as, certainly as the 18th century, when really smart people could aspire to having a fairly good understanding of just about everything.”

“Fifty years after writing The Responsibility of Intellectuals, [Naom] Chomsky remains vigorous and shockingly productive, and — in the dawning age of President Donald Trump — one can only hope he has a few more years left,” the poet and novelist Jay Parini writes on Salon.

“In a recent interview, he said (with an intentional hyperbole that has always been a key weapon in his arsenal of rhetorical moves) that the election of Trump ‘placed total control of the government — executive, Congress, the Supreme Court — in the hands of the Republican Party, which has become the most dangerous organization in world history.’

Chomsky acknowledged that the ‘last phrase may seem outlandish, even outrageous,’ but went on to explain that he believes that the denial of global warming means ‘racing as rapidly as possible to destruction of organized human life.’

I don’t know that, in fact, the Republican Party of today is really more dangerous than, say, the Nazi or Stalinist or Maoist dictatorships that left tens of millions dead. But, as ever, Chomsky makes his point memorably, and forces us to confront an uncomfortable situation.”

“We must recognise that Europe’s (and the world’s) Great Enrichment was in no way inevitable. With fairly minor changes in initial conditions, or even accidents along the way, it might never have happened. Had political and military developments taken different turns in Europe, conservative forces might have prevailed and taken a more hostile attitude toward the new and more progressive interpretation of the world. There was nothing predetermined or inexorable in the ultimate triumph of scientific progress and sustained economic growth, any more than, say, in the eventual evolution of Homo sapiens (or any other specific species) as dominant on the planet,” Joel Mokyr, the Robert H Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences and professor of economics and history at Northwestern University in Illinois, writes in How Europe became so rich.”

The triumph of scientific progress and sustained economic growth was no more predetermined than the evolution of Homo sapiens as dominant on the planet

“One outcome of the activities in the market for ideas after 1600 was the European Enlightenment, in which the belief in scientific and intellectual progress was translated into an ambitious political programme, a programme that, despite its many flaws and misfires, still dominates European polities and economies. Notwithstanding the backlash it has recently encountered, the forces of technological and scientific progress, once set in motion, might have become irresistible. The world today, after all, still consists of competing entities, and seems not much closer to unification than in 1600. Its market for ideas is more active than ever, and innovations are occurring at an ever faster pace. Far from all the low-hanging technological fruits having been picked, the best is still to come.”

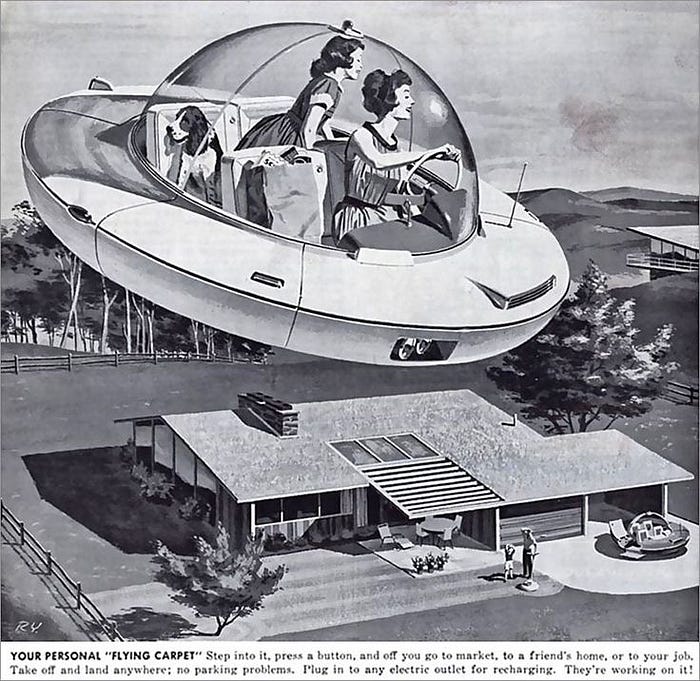

For the past 10 years, photographer Jade Doskow has been documenting the architectural remains of former World’s Fair sites — among the planet’s most curious monuments. Some of these designs and sites are world renowned and remain much admired; think of Buckminster Fuller’s New York dome and Seattle’s Space Needle. While others are now plainly ludicrous, such as the McBarge: the McDonalds restaurant on a barge that graced Vancouver’s ’86 Expo. This grand testament to future technology and architecture of mid-80s Canada now sits anchored, empty, sinking in the city’s False Creek.

It’s that oddness and faded hubris that Doskow captures in her photographs, which are collected in a new book, Lost Utopias, alongside essays by Richard Pareand Jennifer Minner, which reflect on the history of the World Fair. (source: TheLong+Short)

Dunelm House, a brutalist gem once graced by Thelonious Monk and “the greatest contribution modern architecture has made to the enjoyment of an English medieval city,” according to an English Heritage report on Durham, is in need of renovation, not demolition.

“The building’s design, by the Architects Co-Partnership in collaboration with Arup’s engineering company, keeps returning you to considered views of the bridge and the cathedral while continuing to play in lesser keys with the themes of heft and lightness,” the architecture critic of the Observer, Rowan Moore, writes in Save Dunelm House from the wrecking ball.

“The ceiling of the cafeteria is satisfyingly sculpted; its walls cut away at the corners to allow windows to wrap round. Irregularly placed mullions set up vibrating rhythms. A consistency of material and detail, inside and out, unifies the complexity of the spaces and enhances the sense that, as much as architecture, this is abstracted geology.”

Next week the Royal Academy of Arts publishes Lost Futures, a book by its former architecture programme curator Owen Hopkins on the disappearing architecture of postwar Britain. The book will show buildings that were awkward, cussed and sometimes unsaveable, but also majestic, romantic and unrepeatable, like Trinity Square car park in Gateshead, Pimlico school in London, and Birmingham Central Library. Contemplating these works, “it’s hard not to feel that a layer of British history is being filleted away and that the evidence is being removed of a heroic period in British architecture,” says Moore.

“The idea of a particular technology, whether it’s the internet, or genetic engineering, or artificial intelligence, mandating a particular future is a very dangerous idea.” — Yuval Noah Harari